Building a healthier future

For 50 years, Professor Janet King and Rausser College’s accredited dietetics programs have shaped nutritional research, policy, and practice.

The Great Depression was a time of unprecedented economic hardship in the United States, with millions of Americans struggling to afford basic necessities like food. Since then, food assistance programs have helped eliminate hunger nationwide and fortified staple foods like cereals have emerged as a tool to prevent global malnutrition and other deficiencies.

[image caption]

“An individual’s food intake supplies the essential nutrients, vitamins, and minerals required for three important bodily functions,” said Janet King, a professor of the graduate school in the Department of Nutritional Sciences and Toxicology. “They provide the materials to build and maintain the body, act as regulators for key metabolic reactions, and provide the energy to sustain life.”

Rausser College of Natural Resources researchers like King have advanced dietetic and nutritional research for more than a century and translated those findings into policy and practice. They helped set nutritional guidelines and dietary allowances, isolated essential nutrients that govern bodily functions, and made seminal contributions to the scientific understanding of metabolic disorders. But within the past few decades, a new challenge has emerged. Obesity rates have increased since the start of the century, as have rates of chronic diseases like high blood pressure and diabetes. Eradicating hunger and malnutrition is no longer just enough—centering health and well-being throughout the process is becoming increasingly important.

Addressing this challenge is something that King has worked toward throughout her career. Her research has identified ways to improve prenatal health and could hold the key to combating zinc deficiency—which affects hundreds of thousands of children annually—across the globe. And as inaugural director of the department’s accredited dietetics program, which launched its pilot in 1971, King laid the foundation for hundreds of students to become registered dietitians.

Now, more than 50 years after its launch, the College welcomes the inaugural class of its clinically-focused Master of Nutritional Sciences and Dietetics (MNSD): a graduate program that builds on the legacies of King and other researchers by training students to translate scientific research into practical solutions for addressing nutritional challenges and promoting health and wellness.

A legacy of Impact

Rausser College and its predecessors have been at the forefront of nutrition since 1868 when the College of California and the Agricultural, Mining, and Mechanical Arts College merged to form the University of California. At that time, chemists associated with the Agricultural Experiment Station conducted foundational research on the positive dietary role of vitamins, minerals, and protein; and the negative role of cholesterol and fats.

As the program evolved, it was in UC Berkeley labs where anatomists Herbert Evans and Katherine Bishop discovered vitamin E, an essential nutrient necessary for vision, reproduction, and the health of your blood, brain, and skin. Robert Stokstad first isolated folic acid, which is vital for red blood cell formation, and molecular oncology pioneer Leonard Bjeldanes uncovered the mutagens and carcinogens associated with cooked meats and anti-carcinogens in Brassica vegetables.

[image caption]

Outside the lab, chemist Myer Jaffa—who would eventually become the first person to hold the title “professor of nutrition” in the United States—laid the foundation for California’s 1906 Food and Drug Law through his work on food chemistry. Professors Doris Calloway and Sheldon Margen conducted some of the first controlled studies on protein and energy requirements, which later helped the United States government introduce Recommended Dietary Allowances. Pediatrician Norman Kretchmer later emerged as a leading expert in establishing the scientific basis of pediatric nutrition.

Within the classroom, Professor Agnes Fay Morgan, who joined the Berkeley faculty in 1915, helped develop the University’s first scientific curriculum in nutrition and dietetics. A 1934 catalog referenced a hospital dietitian’s training course, and the University offered a curriculum in hospital dietetics in 1954. By the 1960s, the Department of Nutritional Sciences began developing a professionally-accredited undergraduate education in dietetics. Development would continue until the early 1970s, when a Coordinated Program in Dietetics—which King helped design and initially directed—enrolled its first cohort.

A pioneering researcher

King grew up on a farm in rural Iowa, surrounded by her two younger brothers and several hardworking adults. She spent her early years observing her father, mother, and aunt as they tended to the family’s crops and raised dairy cows, chickens, and pigs. Having lived through the depression, King’s parents instilled in her the value of food and the importance of having enough to eat. “Food was never wasted,” she wrote in a 2019 autobiography published in the Annual Review of Nutrition. “If two tablespoons of gravy were left at the end of a meal, they were saved in the icebox and added to a soup or stew the following day.”

These early lessons in nutrition also carried over to the family’s farming practices, with her father reading farm magazines and interviewing other swine producers to learn more about diet composition. “My father fed his livestock a particular regimen of food to produce animals with a high proportion of lean tissue or meat,” she said. “That pork would bring higher prices when it went to market.”

King’s biography credits her high school chemistry teacher, Mr. Whitmore, with inspiring her love of chemistry. That affinity for the subject ultimately led her to a dietetics program at Iowa State University, where she explored the relationship between diet and human health through chemistry, biochemistry, physics, and microbiology. She opted to complete her dietetic internship with the U.S. Army after graduating in 1963 to defray the cost of her education.

King transferred to Walter Reed Medical Center in Washington, D.C., for a yearlong internship after completing basic training. She worked alongside staff dietitians who oversaw food service, outpatient clinics, and metabolic research before moving to Denver’s Fitzsimons Army Medical Center in 1964. While there, King oversaw the hospital kitchen, managed diets required by medical patients, was appointed director of the dietetic internship program, and researched the protein and energy requirements of Army soldiers. “But after working as a dietitian in the Army for three years, I knew that I wanted to pursue a career in nutrition,” she said.

[image caption]

While King was completing her undergraduate degree and began her internship, UC Berkeley was expanding nutrition research as a core biological science emphasis. Professor George Briggs was selected as the first chair of the then-newly established Department of Nutritional Science in 1960 and tasked with attracting and recruiting faculty focused on human nutrition. He hired Margen in 1962 and Calloway in 1963, and supported their efforts to convert the third floor of Morgan Hall into a “Penthouse” capable of supporting controlled dietetic studies. Early experiments focused primarily on testing foods designed to be consumed during long-range spaceflight as part of NASA’s Project Gemini, while subsequent inquiries concentrated on various topics like lactose intolerance among adults or the effect of specific foods on the gastrointestinal function of older women.

King spoke with Calloway after leaving the Army in 1967 and subsequently pursued her PhD at UC Berkeley, where she worked closely with Margen and Calloway in their Penthouse. “Since I had managed a human nutrition research program in the Army before coming to Berkeley, I was responsible for planning the diets and overseeing their preparation and consumption by the study participants,” King said. She also collaborated with a UC San Francisco obstetrician on a separate study of the nutritional status of pregnant teenagers, which would influence her dissertation research.

After completing her PhD in 1972, King joined the department that September as an assistant professor. Her early research focused on the nutrition and metabolism of trace elements like zinc, which is now known to be necessary for immune and metabolic functions. “Studies in rats had shown that it was essential for normal growth and reproduction,” King said. “I wanted to determine if the same was true for humans and how much was needed.” At Margen’s suggestion, King worked with Chemistry PhD student Chris Cann to develop a method of measuring stable isotopes of zinc in stool samples taken from penthouse participants.

“We were the first to use stable isotopes for studying mineral metabolism,” she said. “Today, this is the most prevalent method used in mineral research.”

A Model Program

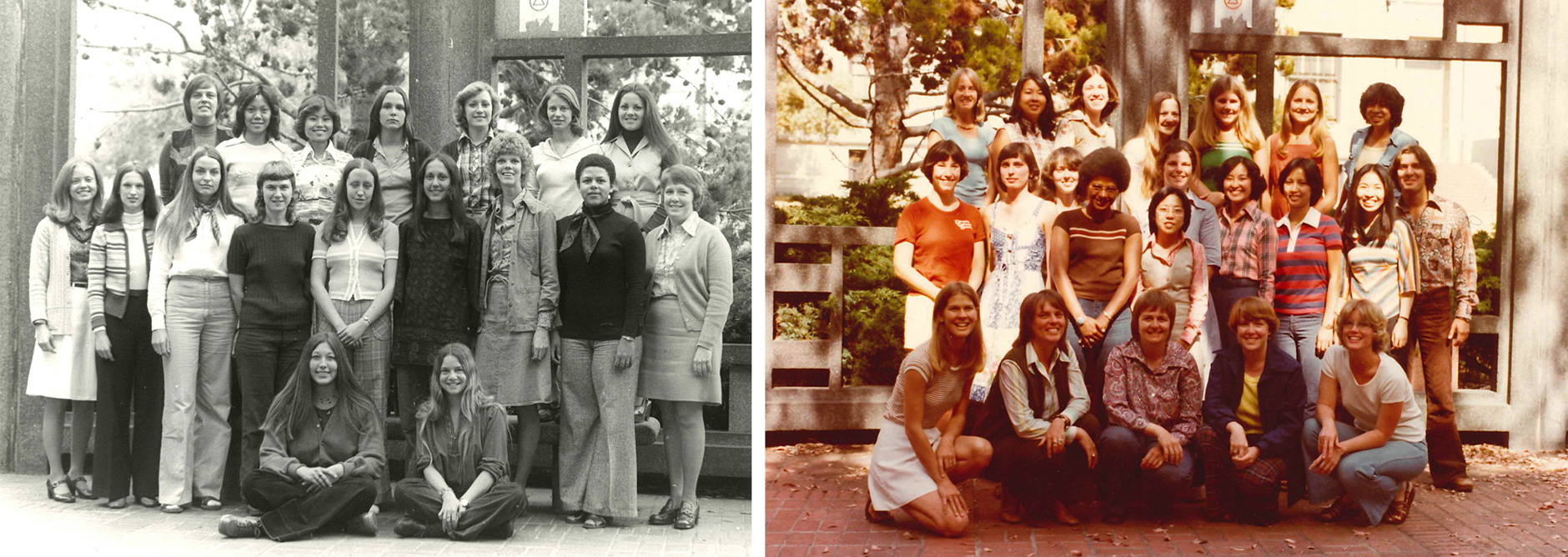

In addition to her foundational research on zinc, King helped modernize dietetics education at UC Berkeley and across the U.S. by developing one of the country's first Coordinated Programs in Dietetics (CPD). She served as the inaugural coordinator for the program, which began operating in 1971 under pilot approval from the American Dietetic Association.

[image caption]

Until then, students who completed coursework in the dietetics major and a yearlong postgraduate hospital internship were eligible to seek licensure as a registered dietitian nutritionist. King’s two-year coordinated program, which received its full accreditation in 1973, provided students with theoretical and experiential training before graduating—eliminating the need for a postgraduate internship. “We taught all of the courses required for the Dietetics major and partnered with hospitals like Alta Bates, Oak Knoll, and San Francisco General to establish rotations that introduced students to clinical experience,” she said.

Faculty including Pat Booth, Nancy Hudson, Susan Oace, and Allison Yates were hired to help manage the program, and two to three working dietitians coordinated student fieldwork. “We became the national model for establishing similar coordinated programs at other Universities,” said King, who served on the Program’s advisory committee from 1980 to 1991. She helped the department explore the creation of a master's degree in clinical nutrition during that period and partnered with the School of Public Health to integrate community-based public health work into the curriculum.

[image caption]

By 1991, the department replaced the coordinated program with a Didactic Program in Dietetics. This program provided the required dietetics coursework for students but required them to independently apply for a dietetic internship after graduating. “UC Berkeley is best known for its research and instruction on metabolic biology,” said Assistant Adjunct Professor Mikelle McCoin, who directed the didactic program for 12 years and now leads the MNSD. “Graduates of our dietetics programs are highly trained in the foundational sciences by leading experts in the field, which sets them down the path to be strong science-minded and evidence-informed dietitians.”

King retired from UC Berkeley in 1994 and joined the Western Human Nutrition Research Center (WHNRC) as its director. She oversaw the initiative to relocate the facility from the Presidio in San Francisco to UC Davis and continued to lead a research program focusing on zinc until resigning in 2003 to join the Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute (CHORI). At CHORI, King worked with researchers who helped her integrate biological mechanisms into nutrition studies and collaborated with clinicians in San Francisco and Oregon. She remained involved in the field of nutrition by chairing the U.S. Department of Agriculture committee responsible for setting dietary guidelines in 2005 and working with postdoctoral researchers.

“Janet helped me bridge my clinical skills as a human researcher and dietitian with my molecular research background,” said Mary Lesser, an assistant adjunct professor of nutrition and former CHORI postdoc who worked with King. “To get the opportunity to work with her was amazing.”

Building a Graduate Program

King retired from CHORI in 2016, where she had served as its senior vice president for research and executive director during her last three years. She returned to UC Berkeley in 2019 as a professor of the graduate school, a position she described in her autobiography as “the ideal job.” That role allowed her to guest lecture, continue her research, and assist in the planning process for the MNSD. As an executive committee member, King helped devise the curriculum, set admissions and scholarship criteria, and influence its direction. “We’ve always embraced new education models that our accrediting agency has to offer,” McCoin said. “Janet was such a big proponent of this change that we were confident it was the right choice.”

[image caption]

Starting Fall 2024, UC Berkeley will offer two dietetics programs. In addition to the MNSD, the School of Public Health recently received accreditation for a Dietetic Internship focused on public health nutrition, policy, and food systems. Students enrolled in that program will be concurrently completing an MPH in Public Health-Nutrition.

Created to satisfy new graduate-level requirements set by the Accreditation Council for Education in Nutrition and Dietetics, the MNSD merges the department’s focus on biological sciences and metabolic biology with the training that students need to become clinicians capable of applying concepts relating to the metabolic regulation of health and disease. Students start with classes to gain a robust professional mastery of advanced dietetics concepts, complete a summer capstone research project, and finish by rotating through several clinical and community settings. “Because nutrition intersects with so many fields of study from basic metabolism through clinical epidemiology, the dietitian of the future needs not only to understand complex science but know how to filter through what is clinically relevant and bring that into their practice,” said Kevin Klatt, an instructor and assistant research scientist in the lab of Professor David Moore.

Lesser, who began teaching in the didactic program in 2013, said the committee welcomed the opportunity to advance its curriculum and reintegrate supervised practice into the program. The department began offering an Individualized Supervised Practice Pathway (ISPP) in 2017 as an alternative to a traditional Dietetic Internship. Dietetics faculty arranged ISPP rotations for all participants at clinical, community, and food service management facilities throughout the Bay Area. Planning these rotations helped the department rebuild relationships with local practitioners, which proved helpful as they prepared to launch the MSND program. “The graduate degree has a strong research and clinical component built in, but we are also tapping into our partnerships with the Bay Area’s clinical, food service, public health, and nutrition providers to train new dietitians at a high level,” she said.

And by shifting to a graduate-level program, the College has attracted a more diverse group of applicants. According to Klatt, students in the inaugural cohort have backgrounds in the biological and social sciences and interests that range from community health and food justice to clinical nutrition and metabolic research. “The type of student that is coming in is much more engaged with a different version of nutrition than what is taught in the “classic” curriculum,” he said. “We’ve had top scholars in their fields come into the classroom as guest speakers and all have commented on how engaged and willing to learn the students are.”

Envisioning A New Future

In early November, the College celebrated the 50th anniversary of its accredited dietetics program with a special lecture by Patrick Stover, director of the Institute for Advancing Health Through Agriculture at Texas A&M University. Past and present students, faculty, and staff in attendance heard Stover—who completed a postdoctoral fellowship with Professor Emeritus Barry Shane before launching his research career at Cornell University after completing—reflect on the program’s legacy and chart its next 50 years.

[image caption]

Stover spoke about transitioning from the current concept of nutrition—primarily concerned with eliminating deficiencies and ensuring nutritional adequacy—to one that bridges the relationship between hunger and health. He highlighted that the integration of advanced molecular techniques with classic nutrition science approaches will create new challenges and opportunities for dietitians to take a precision approach when providing recommendations or interventions to their patients. “You need to enhance the science, but you also need to then advance the translation of that science into practice,” he said.

He also recognized King for her decades of service and contributions. From her years of research and teaching in the department to her continued professional involvement, King’s impact on the field of nutrition spans research, policy, and practice at UC Berkeley and beyond. “There is nobody who has done more in terms of service to the profession for national impact than Janet King has,” Stover said.

Since 1973, hundreds of graduates have used their comprehensive education and hands-on training to excel as dietitians in hospitals, public schools, community health centers, and other settings; pursue advanced degrees; or conduct nutrition-related policy and advocacy work. “Our nutrition and dietetics program is an important part of the College’s mission to serve the people of California, the nation, and the world,” said Dean David Ackerly. “We are incredibly proud of our faculty and alumni for making a difference in the lives and communities of the populations they serve.”

READ MORE

- Maintaining Balance (Annual Review of Nutrition)

- A Penthouse Where Dining Is a Science (New York Times)

- Rausser College launches Master of Nutritional Sciences and Dietetics program

This story is part of a series commemorating 50 years of the College of Natural Resources at UC Berkeley. Read our first story about the 50th Anniversary of the Conservation and Resource Studies program and look for more stories in 2024.